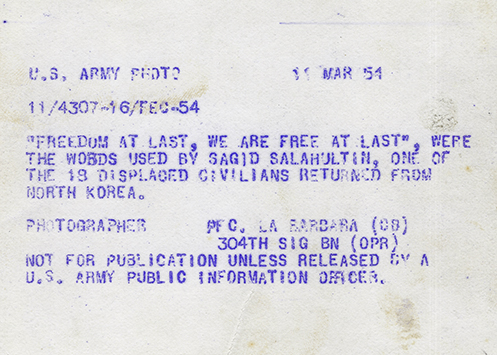

When Dr. Sagid Salah (B.S. ’58, M.S. ’60, Ph.D. ’64) first arrived in Gainesville in 1954, he was 21 years old, had just survived nearly four years as a prisoner during the Korean War, and was technically stateless. He spoke English thanks to a Catholic priest and a missionary who had tutored him in the prison camp but had no high school diploma. What he did have was persistence, curiosity and an unshakable belief that education could open the door to a new life.

The University of Florida opened that door.

Born in Seoul, Korea, in 1932 to parents who had fled the Russian Revolution, Salah grew up surrounded by cultural diversity and conflict. When the Korean War broke out, his entire family was captured and detained in a series of North Korean prison camps for nearly four years. He was just 17 years old. Held alongside American POWs, Salah faced brutal conditions, including a harrowing nine-day, 120-mile winter march through the mountains. Many around him didn’t survive. But during this time, amid unimaginable hardship, Salah developed the resilience and sense of responsibility that would guide him for the rest of his life.

While imprisoned, Salah quietly made a courageous move that helped secure the release of 19 refugees—including his own family—by negotiating with Russian agents under the guise of cooperation. It was a secret he kept for decades before revealing it in his memoir, Stateless.

“We were subjected to freezing temperatures, abuse and starvation,” Salah recalled. “Many didn’t make it out alive. But my experiences taught me never to lose hope, to keep working hard, and to look out for those around me.”

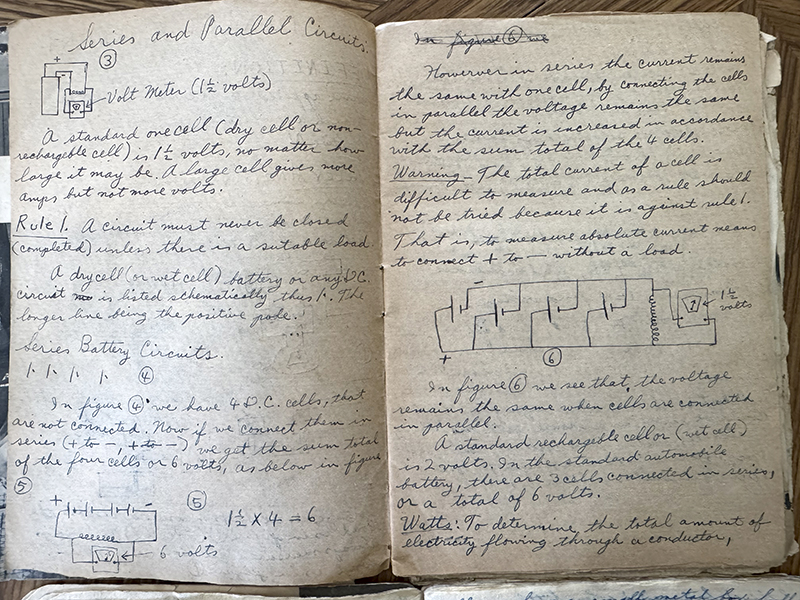

After his release, Salah applied for a U.S. visa and emigrated to the United States, settling in Gainesville with help from a sponsor. Though initially turned away by UF due to a lack of formal academic records, Salah insisted he could handle it because in addition to attending boarding school when he was younger, he had also studied vocabulary and writing in the prison camps. UF Admissions suggested that he go to high school for a semester, and if he did well, they would accept him.

From that point on, he never looked back.

Salah earned a B.S. in chemical engineering with an option for nuclear engineering in just three and a half years. He followed that with a master’s degree and went on to earn a Ph.D. in nuclear engineering. Along with scholarships, he supported himself by working in the school cafeteria, as a teaching assistant, and as an electrical contractor. He lived at the Cooperative Living Organization, forming lifelong friendships, and was moved to see a photo of himself still hanging in their kitchen decades later.

His career took him to the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, Westinghouse’s space nuclear program, and ultimately, the U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission, where he spent decades helping ensure the safety of the country’s commercial nuclear power plants. He also taught nuclear engineering at the University of Maryland, passing on his passion for science to a new generation.

Now in his 90s, Salah lives in Northern Virginia with his wife, Ravile. He’s still curious, still traveling, and still looking up — literally. As a longtime Northern Virginia Astronomy Club member, he’s traveled the globe chasing celestial events, from solar eclipses in Indonesia to the Aurora Borealis in Alaska.

Looking back on his life, Salah reflects with gratitude and perspective. “Being in a POW camp made me appreciate freedom in a way most people never have to,” he said. “Every day since then has felt like a gift.”

His message for today’s students?

“Appreciate what you have. Learn as much as you can. There’s so much potential to improve the world — and it’s brilliant students who will make it happen.”

He credits UF with more than just an education — it gave him a sense of place and possibility.

“I received an excellent education from the University of Florida and am so thankful for the career and life that my education made a reality for me,” he says. “Go Gators!”